We can answer autism’s big questions. The key is hiding in plain sight.

— By Alexander MacInnis

Families affected by autism need answers to critically important questions. They have questions about many things, such as the causes of autism, effective treatments, and prevention of developmental disability in future children. Who will care for today’s children and young adults with autism when their parents can’t do it anymore? Are we allocating research funding appropriately? How might the answers differ for different types of autism?

Unfortunately, despite decades of studying autism and more than 60,000 scientific journal articles about it, we have made surprisingly little progress in answering these questions. We don’t even have a consensus on the basic measurements. We can do better, and we must.

I’m an epidemiologist; I study the causes of good and bad human health. That includes tracking health trends. To answer questions like the ones above, we need to start with the rate of new cases of autism. The news reports every day on the number of new cases of COVID. But we seldom hear about the rate of new cases of autism.

An increase in the rate of new cases would have major implications for our understanding of autism.

- First, if the rate of new cases has increased, it means that the problem is urgent—actively growing larger every year. Research funding should be directed to understanding everything we can about the increase and what to do about it.

- Second, if there’s a real increase in autism, something had to cause it, and that something has to have changed over time. If we identify the factors that caused an increase, we would have opportunities to treat and prevent autism. While many things could help explain an increase, one thing that cannot explain it is genes inherited from one’s parents. Inherited genes can be a risk factor without causing an increase. You’ve probably heard that autism is highly heritable, but heritability is misunderstood. It does not mean that children with autism inherited it from their parents. I’ll explore this in a future post.

- Third, we can use the data on the rates of new cases to forecast the future number of adults with autism. Suppose each birth year has brought more new cases than previous years. In that case, the percentage of older adults with autism will increase accordingly over time. Of course, their parents age too, and at some point, they won’t be able to keep caring for their disabled adult children. That will put a strain—perhaps a huge strain—on our support systems.

How do we measure the rate of new cases?

The standard epidemiology approach for disorders like autism uses a measure called “birth prevalence” [1-3]. That means the proportion of the people born in a specific birth year who have autism. Regardless of when or even whether they are diagnosed, they have autism and were born in a specific year. Birth prevalence is the rate of new cases. The change in birth prevalence over a range of birth years is the trend in the rate of new cases.

Now, here’s something that may surprise you. News reports about a recent CDC report generally say something like, “The CDC  reports that 1 in 44 US children have autism.” Except that’s not what the CDC said.

reports that 1 in 44 US children have autism.” Except that’s not what the CDC said.

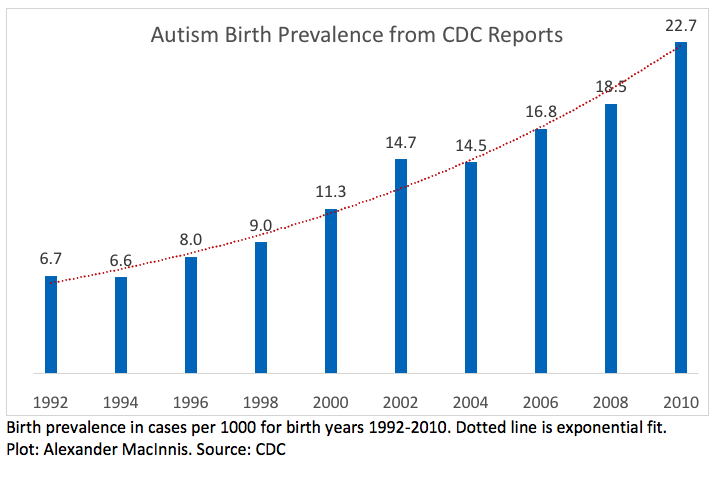

The CDC report published in December 2021 estimated that 1 in 44 US children born in 2010 have autism. It’s right there in the title: “aged 8 years … 2018.” It does not say “all children”—and there’s a big difference. The estimate is actually birth prevalence. The CDC published a series of reports on eight-year-olds covering the even-numbered birth years from 1992 through 2010.

The CDC reports are clear.

These reports show a very strong trend in birth prevalence, from 6.7 per 1000 for 1992 to 22.7 per 1000 for 2010. That is a 239% increase, a 7.4% compound increase per year. The CDC studies are of high quality, and the estimates appear accurate. Numerous other scientific papers show comparable birth prevalence trends in Denmark, California, Minnesota, and Japan. Unfortunately, those reports don’t call it birth prevalence, so the meaning is easily lost.

The logical interpretation of increasing birth prevalence estimates is, of course, that birth prevalence actually increased, making it an urgent public health problem. But by and large, the journal articles and news reports don’t even mention the possibility of a true increase in birth prevalence. Why not?

Why the silence and confusion?

Are these studies sufficient to establish beyond doubt that the birth prevalence of autism has increased dramatically over the last few decades? Not quite. Is it possible that the strong trend in birth prevalence estimates from all those studies was caused by something else? For example, increased awareness or broadening diagnostic criteria? Such alternative explanations are evidently part of many people’s belief systems. But despite widely published speculation, I have searched the literature and have not found any valid evidence that such factors caused the increasing birth prevalence estimates.

Talking about birth prevalence may seem confusing because of another term we hear a lot: “prevalence.” Writers frequently imply that prevalence means the same thing as birth prevalence, but it’s quite different. Prevalence is the proportion of a population—people of all ages—with autism at a specified time. Prevalence doesn’t tell us about the rate of new cases. Comparing different prevalence estimates doesn’t tell us that either, for multiple technical reasons. You might wonder why we aren’t talking about the incidence of autism. I have a post on incidence coming soon.

We can take a new approach.

The scientific journal PLOS ONE recently published a paper of mine [4] that supports all of the technical points you see here. It presents a new method to properly resolve the uncertainty by providing accurate estimates of the effects of all diagnostic factors and the true birth prevalence trend.

What can you do?

- Demand answers to the important questions about autism. Insist that researchers and journalists write clearly about birth prevalence and spell out their assumptions.

- Don’t blindly accept claims that broader diagnostic criteria, greater awareness and other factors have caused the increase we have seen. Claims like that need to be supported by valid scientific evidence that avoids all the pitfalls documented in this paper [4].

- Share this post and these questions. When people you know bring up autism, talk about birth prevalence and what it means.

When we base our understanding on autism birth prevalence, we will finally make meaningful, much-needed progress. Then, we will better understand autism’s causes and the future needs of those with this disorder.

Alexander MacInnis, an independent researcher, has an MS in epidemiology and clinical studies from Stanford University.

References:

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2008.

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018; 392:1789–858. Suppl 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 PMID: 30496104

- CDC Birth Defects Surveillance Toolkit – Birth Prevalence. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/surveillancemanual/facilitators-guide/module-3/mod3-13.html

- MacInnis AG (2021) Time-to-event estimation of birth prevalence trends: A method to enable investigating the etiology of childhood disorders including autism. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0260738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260738

A new perspective an disease that science has failed to discover cause. The effects are felt by millions. Until we discover a cure or prevention society needs to invest in institutions and schools and research. Great paper Sandy

Mr MacInnis not only shows the horrendous increase of autism not only in our country, but in the world, but he also shows how the media skews information they report whether it’s intentional or due to their lack of knowledge or understanding of what they are reporting is unknown. We need to demand answers. We need to demand more research. Unfortunately, if it can’t be cured with a pill, there doesn’t seem to be as much research done.

Alexander – what an insightful post. Thank you for taking the time to analyze and inform of us of this incredibly important issue.

Thanks for this thoughtful analysis of the new CDC data showing increased autism prevalence. In the severe autism community, I hear an equal amount of calls for investigating the increase as I do dismissals of the increase as simply a result of expanded diagnostic criteria and awareness. You have really put a fine point on the lack of data to suggest the latter. I believe these two camps can agree that what is urgently needed is more granular data on cases of autism. The CDC needs to track other data points such as, intellectual disability, level of supports needed, communication impairment, and behaviors. Without this, it will be difficult to discover the cause of the increase in autism or make projections about the future cost of caring for those who are severely disabled it.

Alexander – This is a great paper. Thank you for writing and helping get out this vital information.

Do any of you actually have Autism?

I do and I find this post extremely offensive

I am proudly on the Autism spectrum and I was appalled by this article

I would think that such a progressive city like San Francisco would have an Autism Society that veers towards acceptance rather than simple awareness

I am definitely part of the group of people that believes that Autism shouldn’t be referred to as a disability, as to me it feels extremely hurtful, like telling a gay person that them being gay is a disability, disorder or even worse, a disease

Alexander, your article speaks about autism as if it were a disease, comparing it to COVID, and making no mention whatsoever of the positive attributes of autism, such as savant syndrome

Yes, there are severe cases that require medical assistance, but speaking of autism as a disease is borderline discrimination in my opinion as an individual with Autism

The comments are also extremely hurtful and difficult to read for someone like me

In my firm opinion any article about Autism should be written preferably by someone with Autism themselves or at the very least someone with an extensive knowledge of Autism, not a neurotypical (for all we know) epidemiologist

It feels like old white men writing about women’s rights or old straight men writing about being gay, take your pick

Someone in the comments even mentions how they feel like there has been a “horrific increase” in Autism in recent days

I find it shameful that an Autism Society organization in a progressive city like San Francisco would allow an article like this to be published on their website, which as a matter of fact seems to promote awareness over acceptance

Thank you, George, for sharing your feelings on this topic.

To all self-advocates who are offended by searches for answers: Please find in your hearts some compassion for those who are much more severely affected by autism than you. They may well have a different type of autism. Here I’m referring to people who cannot advocate for themselves, cannot tell their own stories, cannot choose an Autistic identity, cannot take care of themselves, and cannot live independently. Many cannot have competitive employment, let alone professional jobs. Many cannot even tell you where it hurts when they are obviously in pain. For them, autism is a serious problem indeed. That does not make it a disease and I never called it that.

Please also have compassion for the people, primarily parents, who dedicate themselves to the loving care of their seriously disabled children 24/7/365, taking full responsibility for them. It’s much harder than you’d think. They are in an extremely difficult situation. There is a grave lack of useful solutions, medical or otherwise. Those who have not experienced this first hand cannot understand it. Nobody knows what will happen when the parents can no longer care for their disabled children. I am one of those parents, and that is why I changed careers and became an epidemiologist. Countless parents I know have already looked high and low and tried just about everything. They desperately need real solutions. Pretending there isn’t even a problem only makes matters worse.

As the classic railroad crossing sign says, “Stop, Look and Listen.”

I have similar feelings but I don’t feel quite as strongly. I do agree that it is frustrating that everyone who wants to help Autistic people view it as a disease. I am less independent than I probably would be if I were nurotypical but that is because I developed anxiety and struggle to cope with sensory processing dissorder but that is (mostly) because I was diagnosed late.

Alexander, I appreciate your response, however you are still not acknowledging that Autism is a Spectrum and not a gradient, I personally don’t really like the term “Severe Autism”, I prefer to use high support needs

Each autistic person has their own varying levels of certain conditions associated with their specific case of autism

Because of this it doesn’t make sense to think of autism as a scale because it is a spectrum of many different conditions, not just one condition itself

I do acknowledge that as a low support needs autistic person I will never fully understand what it is like to be a high support needs autistic person, however I am still autistic and there are many other autistic adults like me who are also low support needs but their voices deserve to be heard as well

I never meant to disrespect hi support needs Autistics or parents like yourself

I apologize if I came off in a harsh manner and I do really appreciate you taking the time to respond to my message

I understand that you didn’t directly call autism a disease, however comparing it to Covid, which is a disease, did make me feel offended but I do understand that wasn’t your intention

My goal is to try to remind everyone that no case of autism is exactly the same, it is a spectrum and everyone is different

We must acknowledge that many autistics, even those that do struggle with high support needs there are also positive traits that are sometimes missed or overlooked

I really hope I’m not coming across in a bad way and I would be more than happy to hop on a call with you and explain exactly what I’m trying to say

Alexander, I trust that you must be a great father and you probably want to be able to communicate with your son, so I highly encourage you to try to do so, I know it must be difficult if he is not able to speak, but please remember that speaking isn’t the only way people communicate, try to see if he can write, use hand gestures or anything else, letting people express how they feel is key in any situation

Many autistics often go through life without being given the chance to communicate for themselves and I think that is very sad and needs to be changed

I also want to address the harmfulness of using functioning labels

For those of us like myself who have lower support needs we are often invalidated because we don’t fit the description of what certain people consider Autistic to be

This is because we have the privilege of being able to mask our autistic traits, which is not something that we like to do, but is sometimes necessary to get by in a largely neurotypical and ableist society

We still struggle with a lot of things such as reading peoples nonverbal language and many other things that would be very hard for neurotypicals to understand

Please don’t refer to low support needs autistics like me as high functioning

That is a problematic language because it ignores the struggles that we still have to deal with despite having the privilege of being able to mask our autistic traits (despite that not being something we want to do, more something that we have to)

I wish you and your son nothing but the best

What about the Swedish study that shows that the prevalence of Broad Autism Phenotype has remained stable as diagnoses have increased? (Support for the idea that broader criteria for diagnosis of ASD is the reason for increases in diagnoses… checklist diagnoses are also cited as a reason for the inflation both because they are faster and because more clinicians are able to perform them)

Hello RLC. It seems you may be suggesting what Eric Fombonne and others call “overdiagnosing.” Bryna Siegel talks about checkbox diagnoses and diagnosing for dollars. Overdiagnosis means false positives. That is, people getting an ASD (or other autism) diagnosis even though they don’t actually meet the criteria for diagnosis of the disorder. There is at least some evidence of it. It can be challenging to measure rates of false positives accurately.

I suspect that the Swedish study you are referring to is Lundstrom 2015 in BMJ. It compares the prevalence of the autism phenotype — i.e., the symptoms underlying the diagnostic criteria, not the broader autism phenotype — with the prevalence of registered diagnoses, both within the Swedish national patient registry. The results are interesting but inconclusive. The results could come from false positives, broadened criteria or something else. The paper does not examine birth prevalence, which is the essential measurement for trends in autism rates.

The presence of false positives, if they exist, is not evidence of previous false negatives. The hypothesis that true autism rates have remained constant for at least several decades while rates of diagnoses have increased must assume a severely high rate of historical false negatives or an equivalent lack of identification of cases. There is much speculation about that but no evidence of it. There wasn’t even an adequate method to answer that question until my 2021 PLoS ONE paper, cited in the original post. It addresses that topic directly.

The CDC’s reports are different from the Lundstrom paper in many ways. They show birth prevalence for each year studied. All of the CDC reports before the one issued in December 2021 were based on clinical evaluation of documented symptoms, not community diagnoses. (The 2021 report used the CDC’s new method of relying on community diagnoses.)

Please have a close look at the report “Autism in California 2020, A report to the public,” on this site: https://sfautismsociety.org/californias-autism-crisis/. It is based on California Department of Developmental Services (DDS) data. DDS criteria for autism diagnoses requires both meeting the criteria for autism (effectively, autistic disorder, with the name changing to ASD starting in 2013) and, starting in 2003, the requirement for “significant functional limitations” in at least 3 out of 7 areas. See page 5 of the report for details. The report shows cases by birth year, that is, birth prevalence. It would be hard to make the case that the DDS data results from false positives or broadening criteria.